Following the famous argument of prof. Anis H. Bajrektarevic ‘No Asian century without pan-Asian multilateral settings’ which was prolifically published as policy paper and thoroughly debated among practitioners and academia in over 40 countries on all continents for the past 15 years, hereby the author is revisiting and rethinking this very argument, its validity and gravity.

In the XXI century, it was impossible not to notice the rapid economic growth of Asia, given that the growth rates of each of the national economies of the region exceed those of the Western countries. Asia’s economic resurgence and cumulative financial strengths over the last two decades have largely contributed to the global shift of power to Asia [Medcalf, 2018]. However, the assertion about the beginning of the Asian century is still vague.

Considering the history of the region and its current geopolitical status-quo, one should remember that Asia flourished because the Pax Americana period after the end of World War II, which provided a favourable strategic context. But now the twists and turns of US – China relations are raising questions about the future of Asia and the structure of the emerging international order.

For a long time, Asian countries have taken the best of both worlds, building economic relations with China, and maintaining strong ties with the United States and other developed countries. Many Asian states for a long time have considered the United States and other developed countries as their main economic partners, while currently they are increasingly taking advantage of the opportunities created by China’s rapid development.

Due to the new geopolitical situation, the countries of the East Asia region are concerned that, being at the intersection of the interests of major powers, they may find themselves between two fires and will be forced to make difficult choices [Rsis, 2021]. In this regard, countries understand that the status-quo in Asia must change. But whether the new configuration will further prosper or bring dangerous instability remains to be seen.

It is worth noting that Asian countries view the United States as a power present in the region and having vital interests there. At the same time, China and India are immediate and close reality. Asian countries don’t want to choose between them. And if they face this challenge – Washington will try to contain the growth of China or Beijing will make efforts to create an exclusive sphere of influence in Asia – they will embark on the path of confrontation that will drag on for decades and jeopardize the highly-discussed Asian century.

An important element that can resolve the issue of the status-quo in the region is the fact, that the largest world’s continent must consider creation of the comprehensive pan-Asian institution, as the other major theatres do have in place already for many decades (i.e., the Organization of American States – OAS (American continent), African Union – AU (Africa), Council of Europe and Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe – OSCE (Europe)).

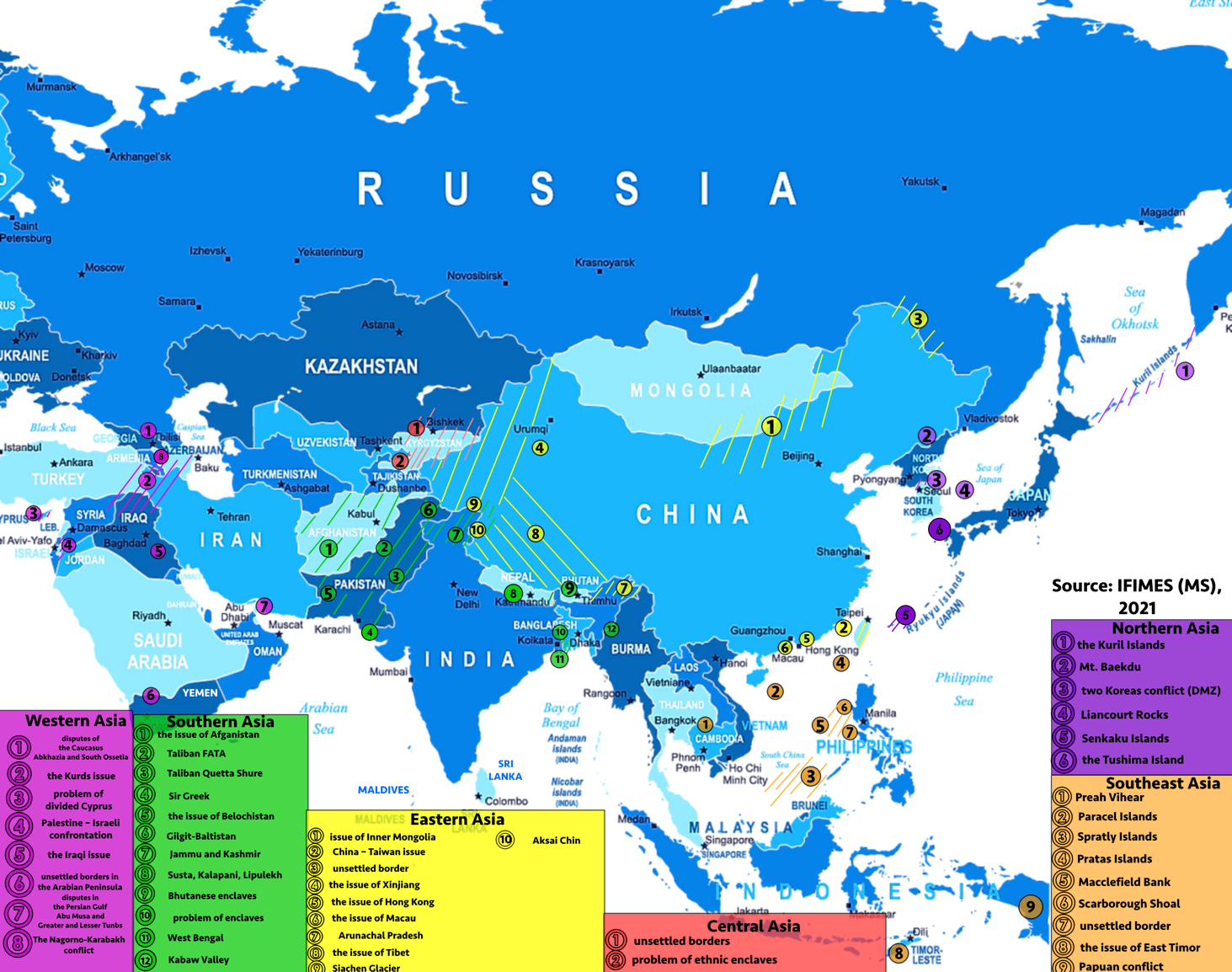

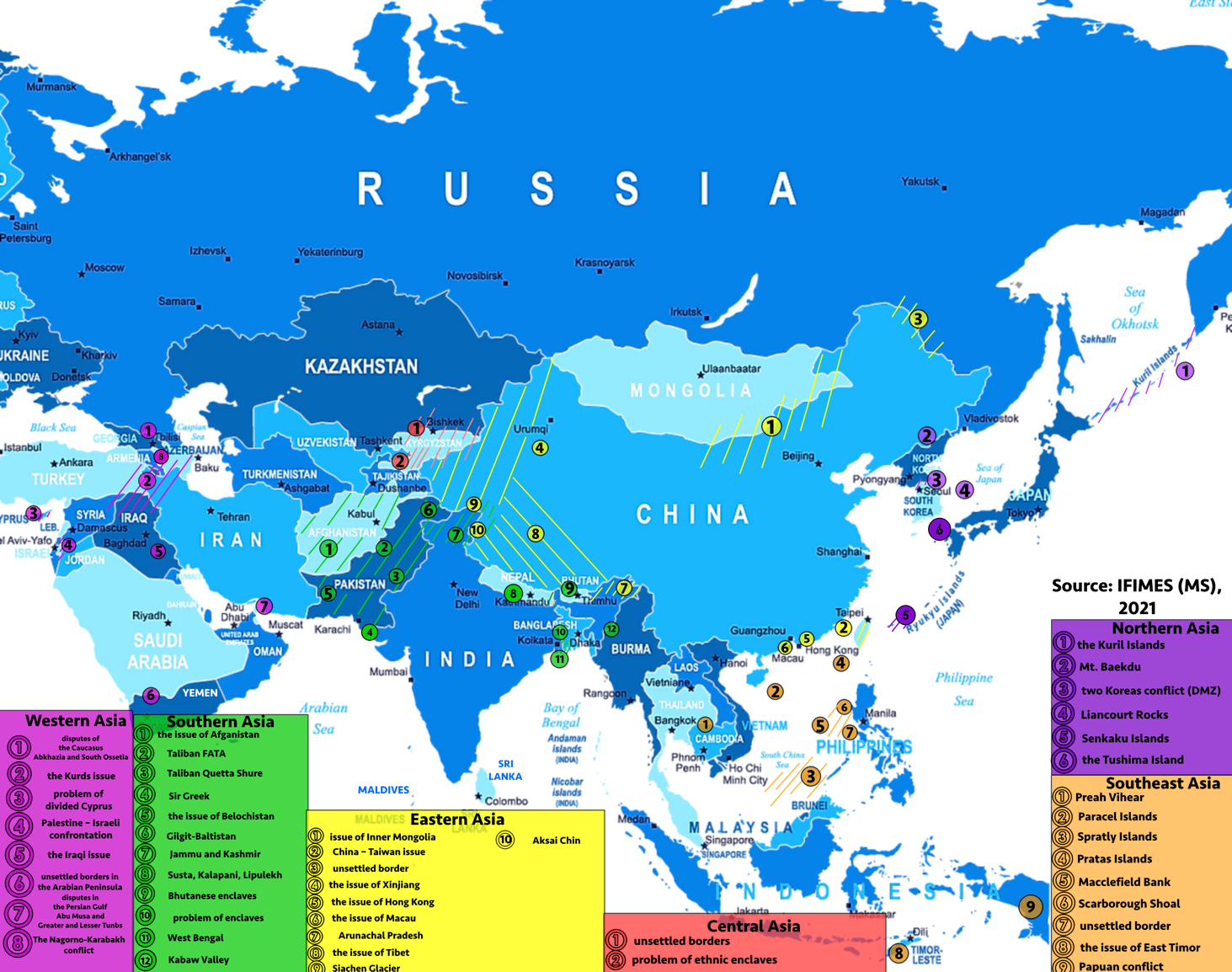

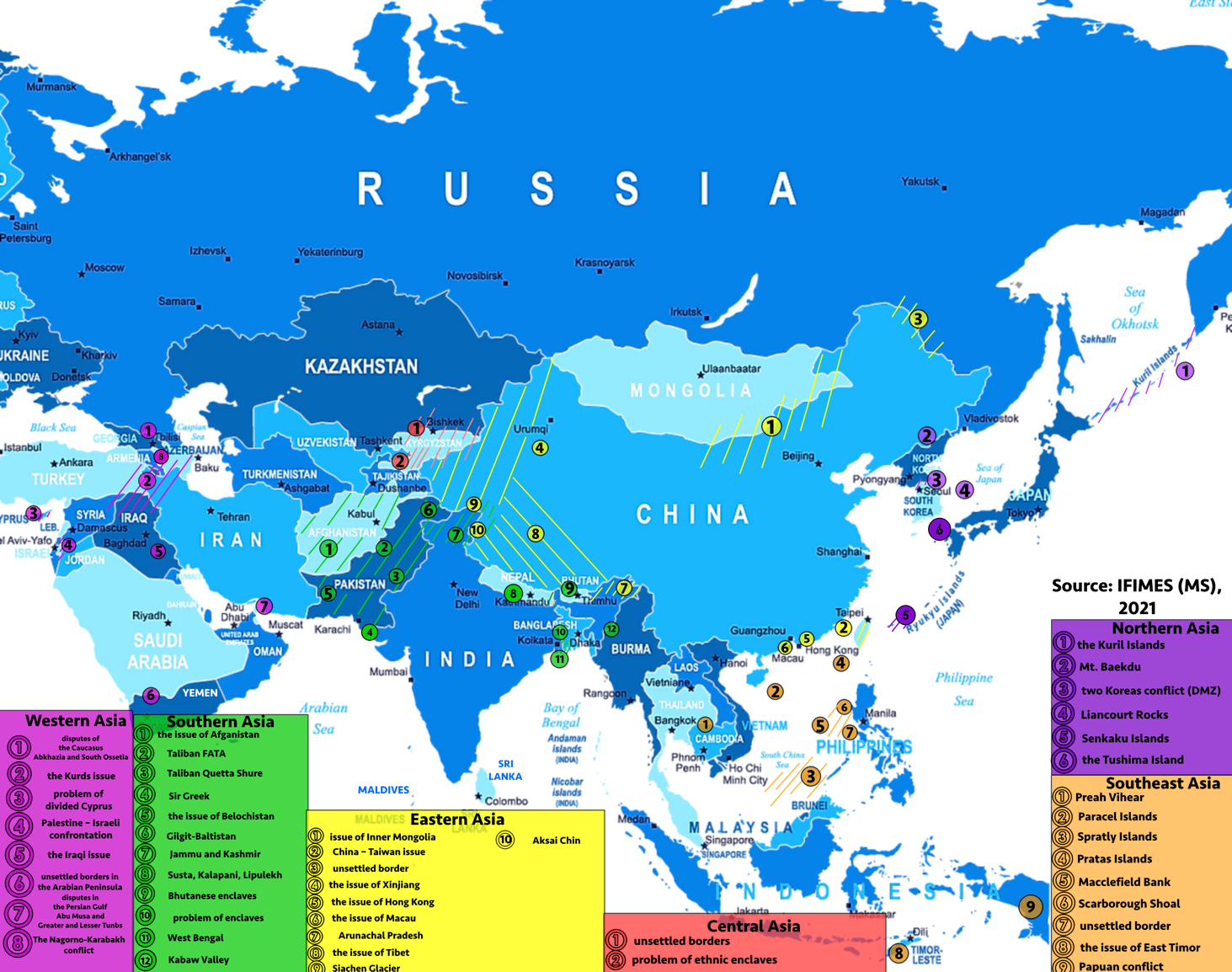

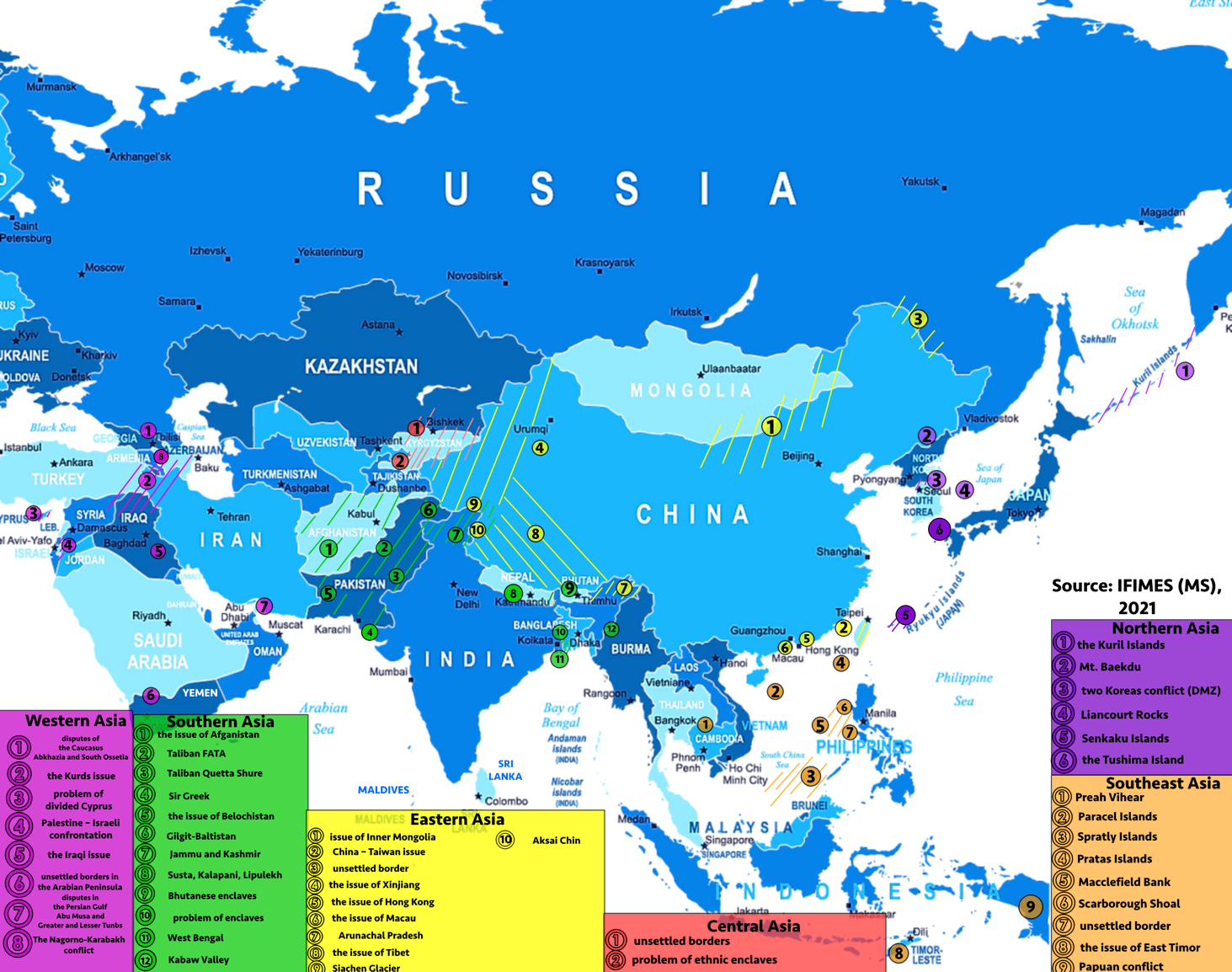

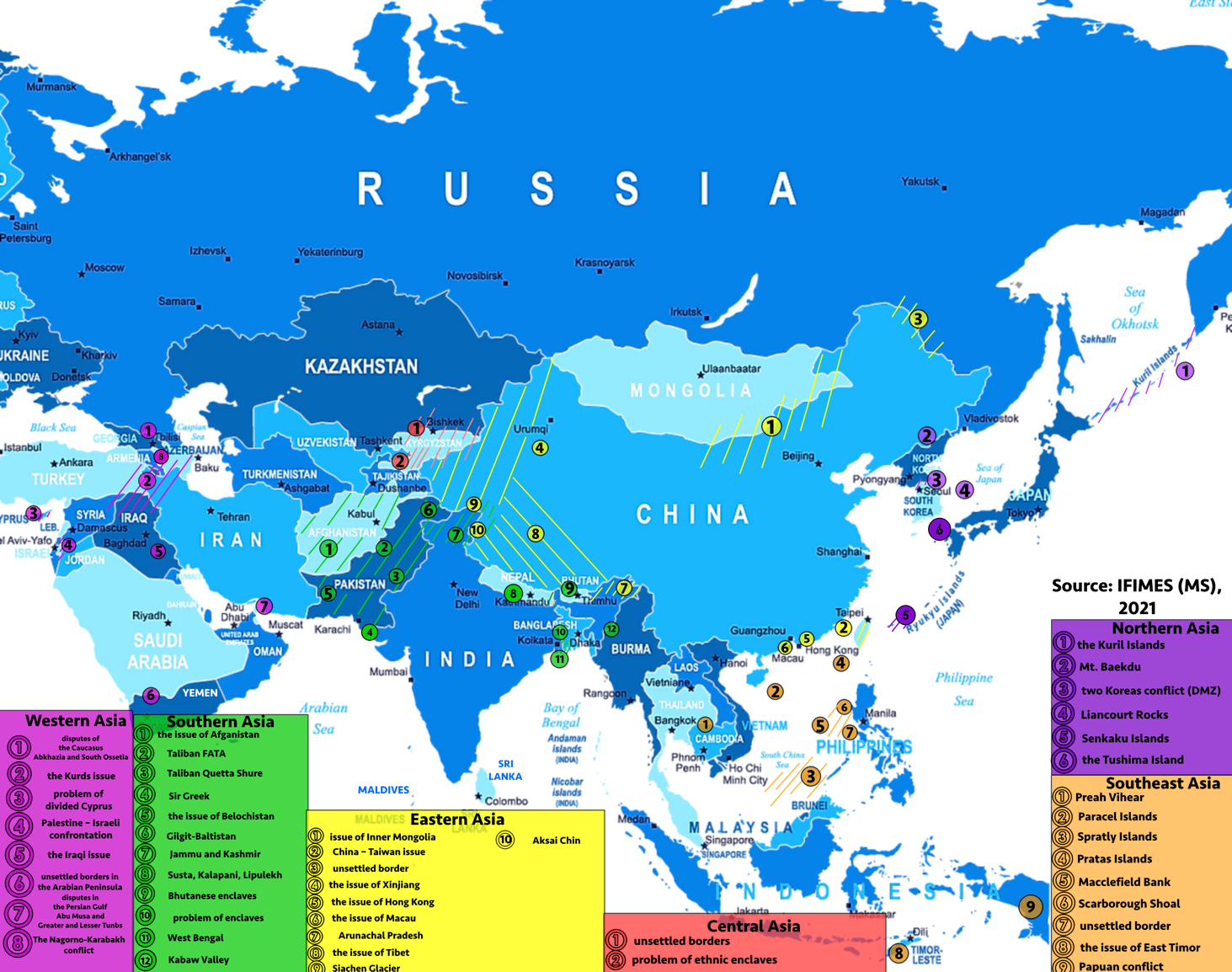

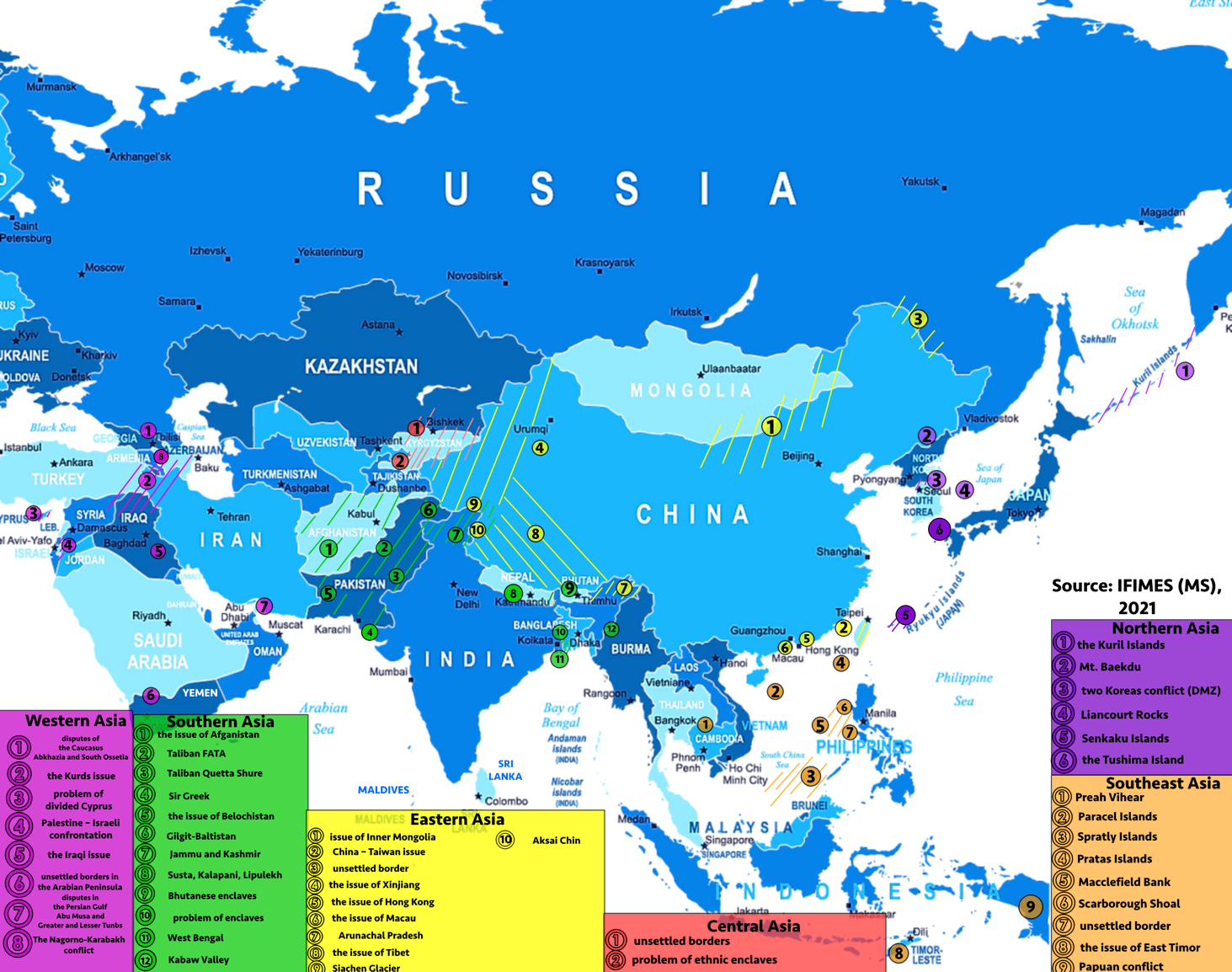

The steps taken by the countries of the leading regions of the world to create a single market and a zone of co-prosperity in recent years have given rise to a desire for consolidation among the leaders of Asian countries [Frost, 2008]. Thus, today Asia is a place of concentration of the largest integration groupings, including the Asia – Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), its’ countries are members of large organizations: the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC), Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), BRICS, G-20, G-8, E-7. These integration groupings are closely interconnected, widely diversified (Commonwealth of Nations) or specialized (OPEC). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that in Asia there is still the absence of any pan-Asian security/ multilateral structure, which leaves many issues of cooperation between countries (especially in the field of security and interstate territorial disputes) unresolved [Kaisheng, 2015]. Thus, in Asia the presence of the multilateral regional settings is limited to a very few spots in the largest continent [Bajrektarevic, 2013], and even then, they are rarely mandated with security issues in their declared scope of work (see Map 3).

Underlining the importance of the creation on multilateral mechanism in Asia, one need to analyse in details the conflicts’ map of the region.

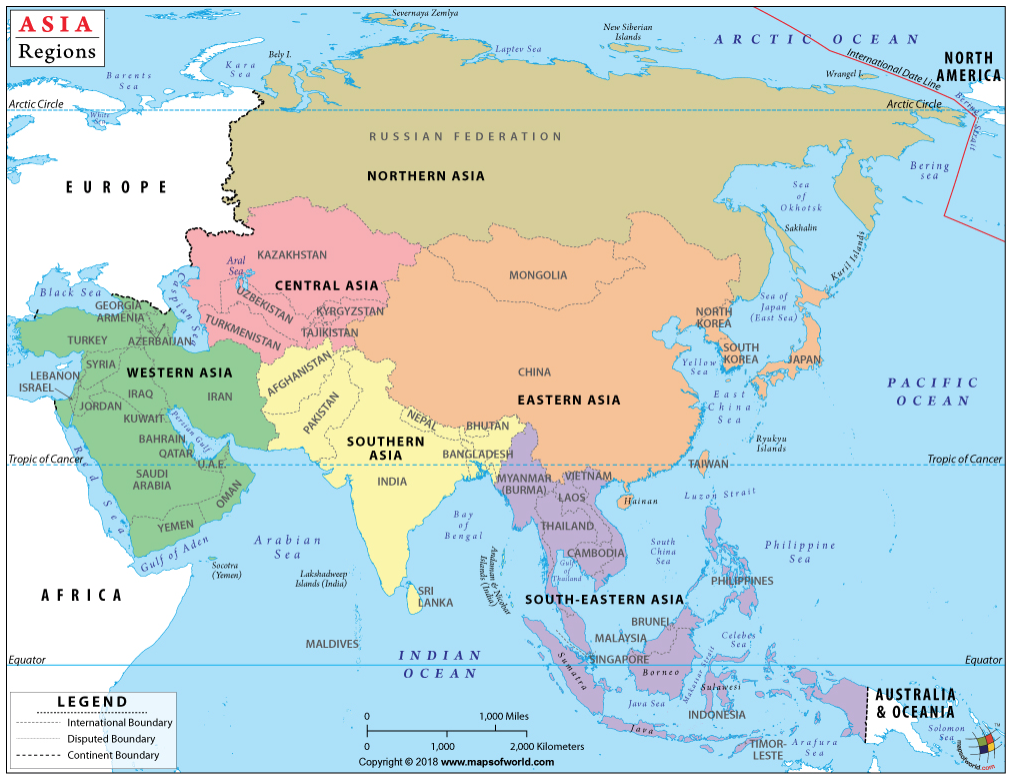

Dividing the region to subregional level Asia as a region includes Northern (Northeast) Asia, China & Far East (Eastern Asia), South – Eastern Asia, Western Asia, South Asia, and Central Asia (see Map 1).

– Central Asia (Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan).

Two post-Soviet Caspian Sea sub-regions – Central Asia and the South Caucasus – have experienced different conflict scenarios. The South Caucasus has been embroiled in protracted, large-scale armed conflicts, while Central Asians have managed to avert a serious armed conflict, remaining largely peaceful despite local, short-term, small-scale clashes, and the existence of factors that may have led – and still may potentially lead – to a serious military conflict (i.e., Armenia – Azerbaijan conflict (The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict). Conflict map of Central Asia (see Map 2) mainly describes the issue of border settlement is the problem of ethnic enclaves, which is a constant factor of tension in relations between Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.

– Western Asia (Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Oman, Yemen, and Iran)

– The situation in (South-) Western Asia, which covers most of the Near and Middle East, has remained very complex and explosive for half a century. This is largely due to the Palestine – Israeli confrontation in Palestine, which escalated in the early twentieth century after the proclamation of the doctrine of creating a “people’s land” for the Jews. The Arab – Israeli confrontation, which began in 1948 (the state of Israel was proclaimed), remains unresolved to this day and is a hotbed of armed conflicts in the region.

Among other main hotbed of instability in Southwest Asia for almost a quarter of a century are the forcibly divided Cyprus, disputed territories between Saudi Arabia and Yemen, dispute over Islands Abu Musa and Greater and Lesser Tunbs (Iran and the United Arab Emirates), the issues of Iraq and Iran, the instability of the Caucasus (Abkhazia and South Ossetia), the Kurds conflicts.

The conflict potential of the region is aggravated by the numerous emigrations to Western Europe (Germany, France) and the United States, whose radical groups often resort to terrorist acts. Such approaches and fierce military operations complicate the overall political climate in such a volatile region (see Map 2).

– Southern Asia (Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Maldives Bhutan, and Bangladesh)

– The area is often referred to geologically, as the Indian Subcontinent and appears to be the area with the highest conflict intensity index in the region. Thus, the biggest country of the region – India – faces territorial issues with many of its neighbours. Over the past 70 years, it has succeeded to resolve its boundary issues only with Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. The undemarcated boundaries with Myanmar, Bhutan and lately with China, Pakistan and Nepal have often flared up into tensions [Kapoor,2020].

The most problematic disputes of the region are between India and China along their disputed border in the Himalayan region (namely disputes over Aksai Chin, Depsang Plains, Demchok, Chumar, Kaurik, Shipki La, Barahoti, Nelang, Pulam Sumda, Sang, Jadhang and Lapthal, Trans – Karakoram Tract, Arunachal Pradesh), which have been worsening in recent years.

India – Pakistan borders disputes (namely disputes over Jammu and Kashmir, Siachen Glacier, Saltoro Ridge, Sir Creek) are the second largest in the region. With continued violence in Kashmir and a heightened threat of terrorist activity by Pakistan-based militant groups, tensions, and concerns over a serious military confrontation between nuclear-armed neighbours India and Pakistan remain high.

Third group of disputes, which is rising of the region’s conflict potential, are India – Nepal border’s disputes (namely disputes over: Kalapani, Susta, Limpiyadhura and Lipulekh of Uttarakhand). It is worth noting that the redrawing of the map covers a relatively small region high in the Himalayas, but it has stirred simmering tensions between two of the world’s biggest powers, India, and China. Thus, involving of the third party (China) into the conflicts of India – Pakistan and India – Nepal is making the tension in the region even higher (See Map 2).

The problem of Afghanistan is also one of the most explosive in the region [Larson,2018]. The war has been going on here for the third decade, it has claimed millions of lives and has long ceased to be an internal affair of this state. Till August 2021 the troops of 14 NATO countries were in Afghanistan fighting the “Taliban” [USIP,2021]. Moreover, several million Afghan refugees settled in Pakistan, Iran and other countries of Asia and Europe, in the United States.

Due to high conflicts level and political regimes of some of the countries of the region, the Western world has identified South Asia as an epicentre of terrorism and religious extremism and therefore has an interest in ensuring regional stability, preventing nuclear weapons proliferation, and minimizing the potential of a nuclear war between India and Pakistan [Rosand et al.,2009].

– Northern (Northeast)Asia (Russia and Mongolia)

In the Far East and North Asia, destabilizing factors remain the Russian – Japanese territorial dispute over the Kuril Islands (Northern Territory), the Korean – Japanese territorial dispute over the Dokdo Islands (Takeshima) (Liancourt Rocks dispute) and the territorial dispute over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyutai) between Japan and China.

– Eastern Asia (China & Far East) (China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, North Korea, South Korea, and Japan)

Of all the disputed territories in the APR, a striking example of the high potential of a formally latent territorial dispute in NEA is the conflict over the Senkaku – Diaoyu Islands, in which Japan and China, the two largest economies and two leading foreign policy players in Northern and East Asia (NEA), are parties to the conflict. This conflict illustrates the essence of modern territorial disputes in the region and the essential information component of such processes.

However, other, equally intractable, disputes cannot be neglected. Among these cases are disputes between Japan and Korea over Dokdo/Takeshima Island and the Kuril Islands that are held by Russia but claimed by Japan. Further regional conflicts involve Korean Peninsula disputes, disputed fishing areas that frequently witness clashes between fishing boats and respective law enforcement agencies. No less important conflict areas of the region are Korean Peninsula and Chinese territories (namely China – Taiwan, the issue of Inner Mongolia, the issue of Tibet (Tibet Autonomous Region) and the issue of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region) (see Map 2).

None of the above-mentioned disputes are likely to be resolved in the foreseeable future. The worst-case scenario is that they continue to plague Japan’s bilateral relations with China, South Korea, and Russia, isolating Japan in the region, and perhaps even resulting in militarized conflict. Though such conflict is unlikely in the disputes with Russia and South Korea, it remains a possibility in the dispute with China.

Both Northern and Eastern regions are the world’s most dynamic areas in terms of economic growth and significance for global trade. While China attracts most attention, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are all strong economies. Add Russia and the US in the mix and the importance of Northeast Asia cannot be overstated. These two regions are characterised by “strategic diversity” where several unresolved territorial disputes threaten to undermine the very source of regional prosperity: maritime trade.

– South – Eastern Asia (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, East Timor, Papua New Guinea, and Vietnam)

In Southeast Asia (hereinafter SEA), compared to other regions, the numbers of unresolved territorial disputes are still considered small, and SEA is considered a relatively safe region with no significant violence going on [Jenne, 2017].

The territorial disputes in SEA consist of the following disputes: the Philippines’ Sabah Claim (The North Borneo), the Ligitan and Sipidan dispute, the Pedra Branca dispute and the South China Sea Conflict Zone also known as the Spratly Islands disputes and conflicts of East Timor and the divided island of New Guinea. Among them the last one (the Papua conflict) – land dispute in which 21 people died (last update as for April 2021[Fardah,2021]) is the latest brutal conflict exacerbated by high-powered weapons, weak governance, and erosion of traditional mores (See Map 2).

The territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea (the Spratly Islands disputes) are considered some of the most complex conflicts in the region if not worldwide. The disputed areas are abundant in natural resources such as gas and oil and carry strategic importance, as roughly half of the world’s commercial shipping passes through them. Their judicial resolution is usually unlikely, and the use of conciliation mechanisms is preferable. Despite this, there is little doubt that the conflicts in the South China Sea will dominate the region’s security agenda for years, if not decades, to come [Avis, 2020]. The intra-ASEAN disputes in the South China Sea will most likely remain dormant for a considerable time to come.

Given the growing number of military expenditures of Asian countries and the presence of many hotbeds of tension, territorial disputes of the entire region, are turning it into one of the most complex problems and potentially explosive challenges, indirectly affecting the interests of most of the states of the Eurasia.

Up to day countries of the region did not create a stable multilateral mechanism which can help them to work out a compromise solution on the issue of legal registration of state borders and territorial claims. This issue is one of the most important, since it can guarantee the territorial integrity of states and ensure non-interference in their internal affairs, as well as represent one of the barriers to external threats to their national security, such as smuggling, international crime, extremist and terrorist movements, illegal migration.

Today, the diversity of the Asian sub-regions, the differences in the political and economic systems of the states, determine the specifics of the formation of integration structures in Asia [Ayson, 2009]. A characteristic feature of integration structures in Asia – in most cases, they are created to jointly solve economic problems, achieve economic integration in the region or sub-regions, but not to solve security issues:

– the Asia – Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

Being an organization with the largest Asian participation, the Asia – Pacific Economic Cooperation engulfing both sides of the Pacific. While created, this forum was planned to become a mechanism for developing global rules for economic and military-political interaction between countries of the APR, but eventually organization turned into a regional integration setting of the Asia – Pacific countries, mainly involved just in economically-related issues [APEC,2021]. Even considering the shifts of the APEC towards resolving political issues (response to security threats), so far this is a forum for member economies not of sovereign nations, a sort of a prep-com for the World Trade Organization – WTO, which is not involved into the solving of security issues of the region.

– the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization, created in 2001, was formed based on the previously existing political association of the “Shanghai Five”: Kazakhstan, China, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan (See Map 3).

While it was mentioned that the main goals were strengthening trust between its participants in the military field, ensuring peace, security and stability in the region, criticism of the SCO largely concerns the failure of its activities, in the fight against terrorism and the protection of regional security [Weitz, 2014]. Some foreign analysts (i.e., Matthew Oresman of the American Centre for Strategic and International Studies) suggest that the SCO is nothing more than a discussion club, claiming something more [Oresman, 2005]. The same opinion is shared by the head of the Institute of Military History of the Russian Ministry of Defence A. A. Koltyukov, who claims that “the analysis of the results achieved by the SCO allows us to characterize it as a political club in which bilateral cooperation still prevails over the solution of regional and world problems. … there is no real cooperation in these areas in countering the threats of terrorism, separatism and the fight against drug trafficking at the regional level” [Kol’tyukov, 2008].

– the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC)

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, SAARC – economic and political organization of eight countries in South Asia is the Indian sub-continent’s grouping, created in 1985.

The main goal of the SAARC is to develop interaction between the participating countries in the economic, socio-cultural, and scientific-technical fields, however, with the accession of Afghanistan (in 2007), the Association began to discuss issues of combating terrorism.

Being an organization, which helps the integrate the region and intensify mutual collaboration between countries-participants, the SAARC is practically a hostage of mega confrontation of its two largest members, both confirmed nuclear powers: India and Pakistan. Additionally, the SAARC although internally induced is an asymmetric organization, considering the size and position of India: centrality of that country makes SAARC practically impossible to operate in any field without the direct consent of India, which is not helping the organization to resolve important security-related issues of the region.

– the Organization of Islamic Cooperation – OIC and Non-Aligned Movement – NAM

Another crosscutting integration settings of the region are the Organization of Islamic Cooperation – OIC and Non-Aligned Movement – NAM.

The development of NAM as a new trend in the system of international relations was laid by the Bandung Conference of 1955, which served as the beginning of the creation of an international organization uniting countries that proclaimed non-participation in military-political blocs and groupings as the basis of their foreign policy. The creation of the OIC in 1969 was facilitated by a series of events that shook the Islamic world, the main ones of which were the defeat in the Arab – Israeli war in 1967 and the burning of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem by Israeli extremists. Thus, initially the creation of these two settings had a security root.

However, as professor Anis H. Bajrektarevic elaborated in his work on “No Asian Century”, they are inadequate forums as neither of the two is strictly mandated with security issues [Bajrektarevic, 2015]. Although both trans-continental entities do have large memberships being the 2nd and 3rd largest multilateral systems, right after the UN, neither covers the entire Asian political landscape – having important Asian countries outside the system or opposing it.

– the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO)

The Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO), which existed in 1995 – 2006, which main goal was to implement the 1994 Framework Agreement between the United States and North Korea and freeze the development of a local nuclear power plant in North Korea, as well as Group 5 + 1 (P5 + 1, E3 + 3) – a forum of six great powers that have united their efforts to prevent the use of the Iranian nuclear program for military purposes, were both dealing with indeed security related issues in Asia. Nevertheless, both settings were created to deter and contain a single country by the larger front of peripheral states that are opposing a particular security policy, in this case, of North Korea and of Iran.

– BRICS

The formation of global governance institutions began with the creation of the G7 in 1975. In 2008, the first G20 summit took place, and in 2009 – BRIC (BRICS since 2011). These informal forums, focused primarily on economic cooperation, do not fully fulfil their obligations to counter protectionism, environmental growth, food security and fairness in the labour market.

These problems exist due to the inability of both institutions to create a full-fledged accountability mechanism to ensure transparency of the processes of implementation of the decisions of the summits.

Also, the BRICS and G-20 are not providing the Asian participating states either with the more leverage in the Bretton Woods institutions or helping to tackle the indigenous Asian security problems.

– the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

This sub-regional political and economic organization was created in 1967, and included Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, and Brunei. The main goals of this organization are the development of economic, social, cultural, and other types of cooperation between the member countries of the Association, the establishment of peace and stability in Southeast Asia (See Map 3).

This organization played an important role in the social and economic development of the Southeast Asian countries, contributed to the growth of their political influence in the region, however, regional cooperation in the field of defence and security within the framework of ASEAN has not yet been activated. Today, it can be assumed that ASEAN can evolve into a “security community” in the sense that none of its members seriously consider using force against another member to resolve contentious issues. But it will not become a “defensive community” because there is no common cultural, ideological, and historical experience. More importantly, there is no threat common to all members. The successes achieved by ASEAN – relative peace, stability, and security – still do not form the basis for broader military cooperation, but rather allow each state to develop on its own way.

Towards conclusions

The creation of sub-regional international organizations is a proof that currently Asian countries are more willing to consult and cooperate with each other on the integration and creating of the zone of co-prosperity issues. Nevertheless, in Asia, there is hardly a single state which has no territorial dispute within its neighbourhood. From the Middle East, Caspian and Central Asia, Indian sub-continent, mainland Indo – China or Archipelago SEA, Tibet, South China Sea and the Far East, many countries are suffering numerous green and blue border disputes (See Map 2).

An equally important factor is the presence in Asia of strong global geopolitical players vying for spheres of influence in the region (China, India, Japan, Russia, and USA).

Currently the APR countries today do not want to choose between centres of power, willing to develop good relations with all partners and at the same time ensure their security. In this regard, the question of the creation of its own comprehensive pan-Asian multilateral mechanism, with the help of which countries will be able to take an active part in the formation of a new world order and take a worthy place in it, is becoming more and more urgent.

The foundation on which Asia – Pacific countries now support regional cooperation initiatives, such as the various Indo – Pacific concepts proposed by Japan, the United States and others, as well as China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”, is built on a policy of peaceful coexistence and containment of the emergence of one strongest leader in the region (many Asian countries believe that promoting the “Belt and Road” is a constructive way to control China’s growing influence in the region [Smotrytska,2021]). Thus, today the behaviour of the countries of the APR region shows that the development of new regional mechanisms does not mean abandoning the existing multilateral structures. These hard-won agreements and institutions continue to provide all countries, especially small ones, a framework to work together and advance collective interests.

Besides the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), there have been other emerging features of security cooperation in Asia that are not necessarily based on geographical groupings but on security concerns and capability [Pejsova, 2014]. These multidimensional developments indicate that security cooperation in Asia is far more complex today than a traditional bi-multi nexus model. The “double-track” approach is now entering into the new phase especially in the wake of various forms of multilateral security mechanisms that have been revealing in recent years in Asia – Pacific.

An analysis of the emerging alignment of forces within the international community allows us to conclude that the very formulation of the question of the Asian century suffers from unacceptable simplification and schematization that does not consider new world realities and the geopolitical structure of the region, that cannot be explained in traditional concepts and categories. And the reality is that the East has already become the supporting structure of the world community, equal in size to the West, and its’ role in the coming century will increase. Moreover, in the East itself, several centres are ripening (China, Japan, India, and a numerically growing group of smaller, but very dynamic new industrial countries), capable of competing on an equal footing both with each other and with the West, if not as a whole, then with its leading powers. But to consolidate the total power of Asian countries the largest continent must consider the creation of its own comprehensive pan-Asian multilateral mechanism. Economic and demographic parts of Asia must be accorded by the new pan-continental setting. On the very institution setup, Asia can closely revisit the well-envisioned SAARC and ambitiously empowered ASEAN fora. By examining these two regional bodies, Asia will be able to find and calibrate the appropriate balance between widening and deeping of the security mandate of such future multilateral organization.

Maria Smotrytska is a senior research sinologist and International Politics specialist of the Ukrainian Association of Sinologists. She currently serves as the Research Fellow at International Institute for Middle East and Balkan Studies (IFIMES), Department for Strategic Studies on Asia (DeSSA). She holds a PhD in International politics, from the Central China Normal University (Wuhan, PR China).

Contact: dessa[at]ifimes.org