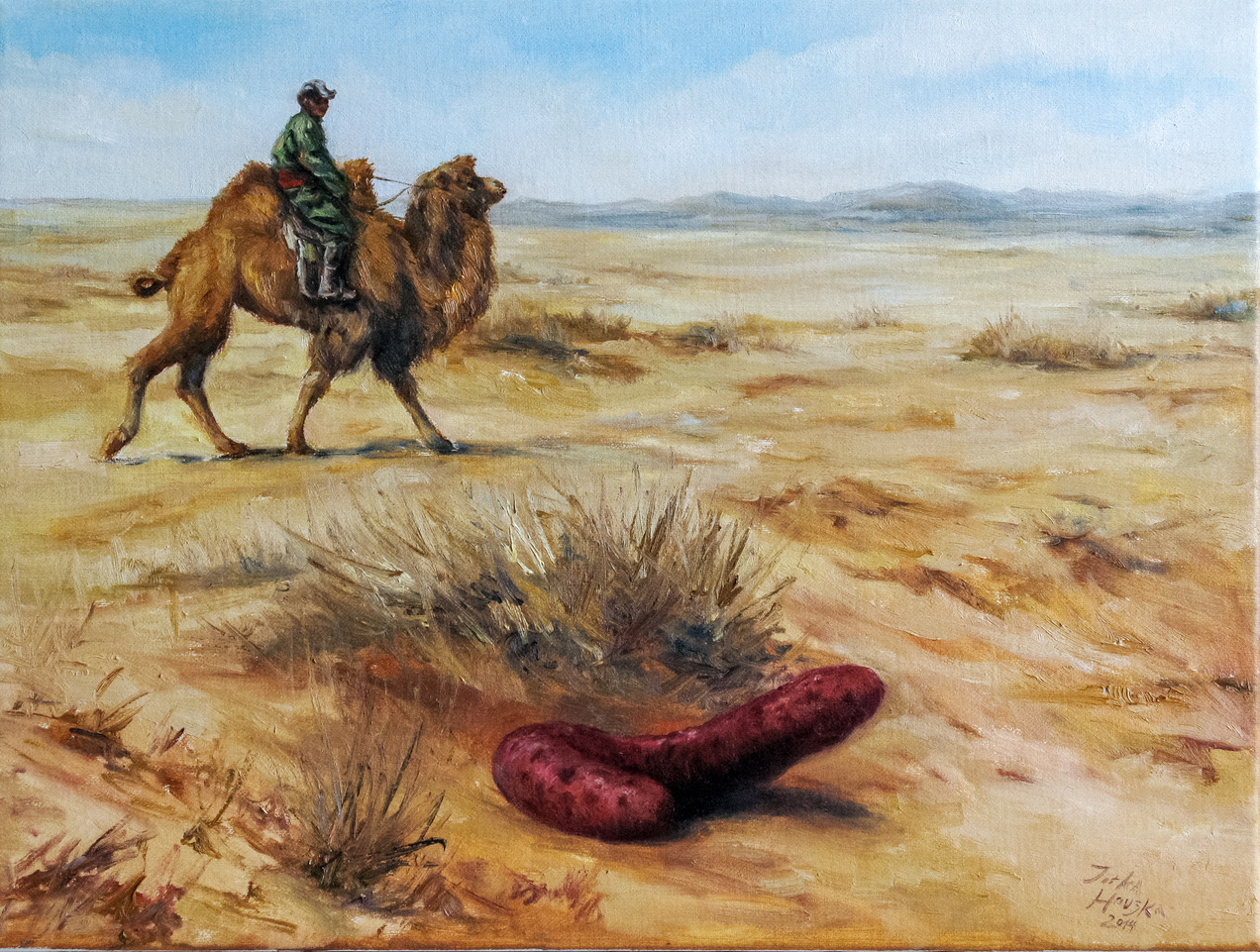

Olgoi-khorkhoi as portrayed by the painter Jiří Houska.

Olgoi-khorkhoi – the mythical killing worm from the Gobi Desert – is perhaps better known today in Czech Republic than in Mongolia itself. It happened thanks to Czech enigmologists, who searched for it in local sand dunes. And on top of that, one of them, the late Ivan Mackerle, gave rise to olgoi-khorkhoi‘s world-wide fame that it gained in sensation-hunting circles.

Today we can say that the origin of the legend of olgoi-khorkhoi was caused by the Tartar sand boa. But the truth is that for a long time it was not known what it was all about.

R. C. Andrews, who led an American paleontological expedition in Mongolia in the 1920s, was the first to report on olgoi-khorkhoi:

“At the Cabinet meeting the Premier asked that I should capture for the Mongolian Government a specimen of the Allergorhai horhai. This is probably an entirely mythical animal, but it may have some little basis in fact, for every northern Mongol firmly believes in it and will give essentially the same description. It is said to be about two feet long, the body shaped like a sausage, and to have no head or legs; it is so poisonous that even to touch it means instant death.”

Tartar sand boa peeks out of the sand. Photo: Miroslav Bobek

Note, that in Andrews’ rendering olgoi-khorkhoi cannot kill at a distance.

In the 1940s, the Russian palaeontologist I. A. Yefremov picked up the topic and portrayed it in one of his short stories:

“…I called the driver and Misha to come back. But they continued running to the unknown animals, and either they didn’t hear me, or they didn’t want to.

I took a step toward them, but Darkhin pulled me back. I broke free from the guide’s tenacious hands and at the same moment I watched the animals. My assistants had already reached them: the radio operator in front, Grisha little bit behind.

Suddenly each of the worms curled up into a ring. At the same moment their yellow-grey colouring darkened, turning into purple-blue and bright blue at the ends. Without a cry, the radio operator suddenly collapsed and laid motionless with his face in the sand. I heard a scream from the driver, who was at that moment running to the radio operator lying about four metres from the worms. A second – and Grisha bent over just as strangely and fell on his side.

His body flipped over, rolled to the bottom of the dune and disappeared from the sight.”

Well, it is a different story!

Yefremov’s short story has also been repeatedly published in Czech – and I am sure that it initiated the interest of Czech enigmologists, among whom the abovementioned Ivan Mackerle stood out. In early 1990s, he searched hard for olgoi-khorkhoi in Mongolia. He was even allegedly trying to drive him out of the dunes by setting off the explosions of small charges. With no result. However, his belief in the existence of a worm, which kills at a distance, was unwavering. At the same moment the testimonies of witnesses he recorded largely support an interpretation that he had even not thought of, namely that the myth of olgoi-khorkhoi arose from encounters between shepherds and Tartar sand boa. For example, the old woman Püret told him:

“ʻI have never seen it myself, but I have heard a lot about it. In the past shepherds occasionally encountered it, but today it is very, very rare. It usually appears after rain, but it rarely rains here. It basks in the sun for two to three days and then it disappears again. In a sea of sand like a fish in water,’ she laughed. ʻUsually, it digs holes just under the ground and on the surface above him the sand is pushed a little bit, so it is possible to see where it is moving. When it wants to attack somebody, it pulls half a way out of the sand. It starts inflating, the bubble on its end gets bigger and bigger until finally the poison squirts out of it.’”

And so, eventhough Mackerle was wrong, he gave rise to popularization of the “killing worm from Gobi” and I dare say that if it were not for him, I probably would not have thought about showing the archetype of olgoi-khorkhoi – Tartar sand boa – in our zoo.