Japan and Ise Grand Shrine

Emperors visit at Ise Grand Shrine

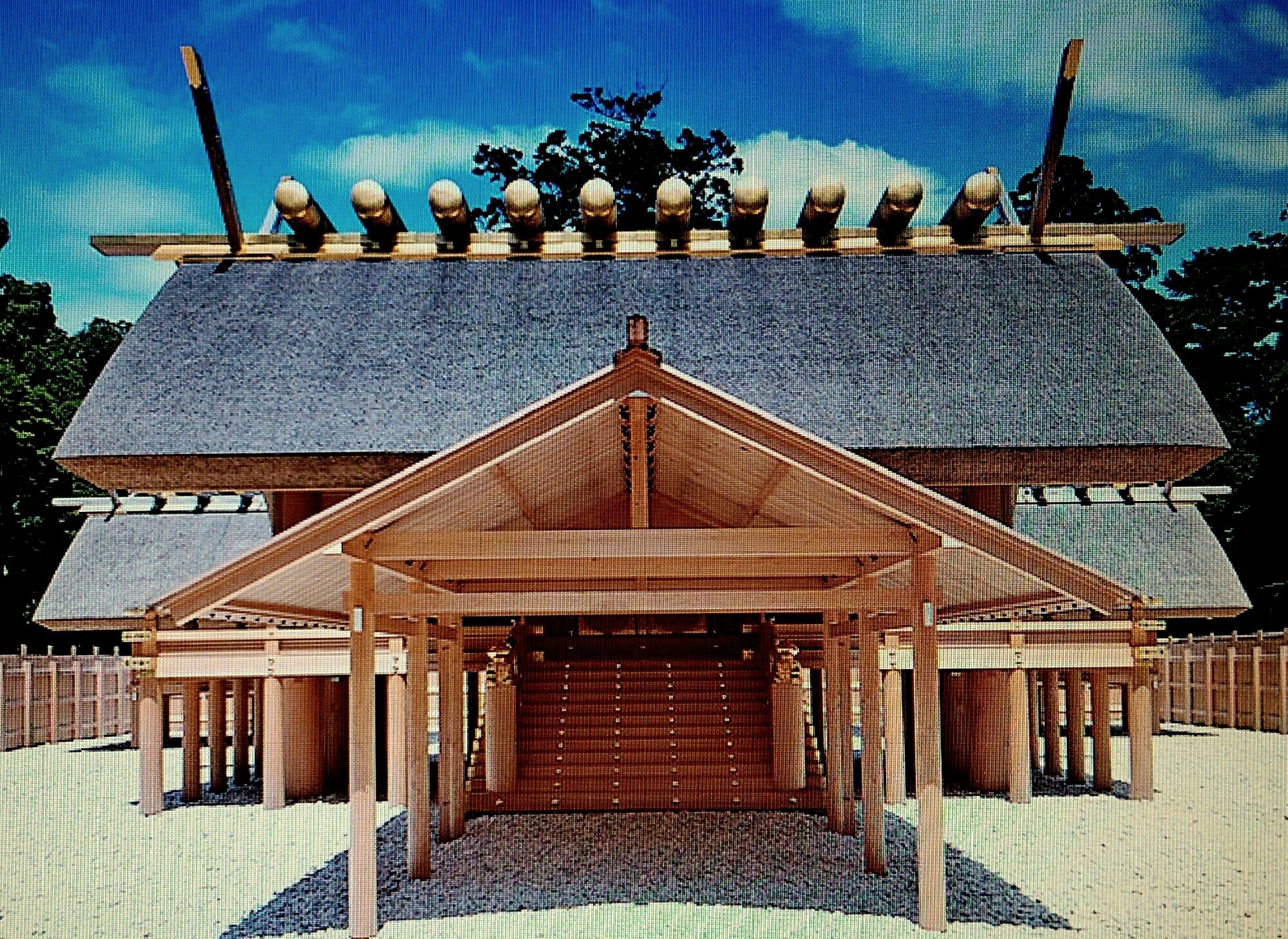

In the Land of the Rising Sun there is a ritual repeated over and over again. In the spiritual heart of Japan, in the south of Honshu Island, every twenty years the Ise Grand Shrine is completely dismantled and rebuilt again with the slightest detail kept. Why is the shrine taken apart and rebuilt again? What sense does it make?

The Ise Grand Shrine is located at the elevated place in the large forest park of great Japan cedar trees. The combination of the beautiful natural landscape, proximity of the mountains, waterfalls, sea bay giving the prettiest pearls of Japan, as well as its isolation, all of this is an indication that the place is strongly saturated with the energy of nature. The Ise Grand Shrine is the most significant Shinto´s shrine in Japan, dedicated to the worship of Amaterasu goddess. The complex actually consists of 123 shrines. It is divided in two parts: Geku or The Outer Shrine is dedicated to the god of nice harvest, The Inner Shrine or Naiku to the goddess of the Sun. The two parts are approximately six kilometres apart and joined by an old pilgrimage road. Each of the two shrines also has a number of other buildings attached, including additional shrines, workrooms, store houses, and other auxiliary buildings. Each has some kind of an inner hall with the main shrine and two additional shrines. The rooms are built on pillars representing the pole of heart. The roofs are not supported by walls but by two columns at each end, set directly in the ground as a symbolic contact with nature and earth. The year of 690 is considered the date of the first ever construction of the shrines in their present form.

As a part of the Shinto tradition the two main buildings of the shrine are rebuilt every twenty years according to the exact plans and using the original technology. There is an empty site beside each building where the new shrines are built first, focusing on the preservation of each detail. Then, while worship is taking place, gods are transferred into the new building. Then, following further worship, the old shrine is dismantled and its parts are distributed among associated shrines all over Japan. It is also a part of Shinto belief of the death and renewal of nature, the impermanence of all things, but also a way of passing building techniques from one generation to the next. Present buildings were rebuilt in 2013 and they represent the 62nd copy of the original shrines.

New construction of the Shrine

So, what is so interesting to see at the place where around 14 millions Japanese come every year? What do we expect to see? Nothing, or rather close to nothing. Why do we come to the place where apparently there is nothing to see? What do the Japanese come to admire to the place where there is nothing more than a fragile construction from unprotected cedar wood, of which you are able to see just a little piece of the roof behind a tall wooden palisade?

Mutsuo Takahashi, contemporary Japanese poet says: There is nothing in Japan. Nothing original. And yet…

The answer lies in the difference of the world view of Japanese (if you wish the Buddhist and concretely here Shinto) belief and the “western”, mainly Christian civilization. For example, imagine the St .Peter´s and Paul´s Basilica in Vatican which enchants us with its magnificence, art of architecture, craftsmanship, splendid decoration, and overall uniqueness. Here, in the Ise Grand Shrine, there is nothing to see, and yet. You can see the very opposite here. The man comes here to fulfil his belief, to listen to his feelings, to sense and contemplate, to enrich his mind and soul with no distraction and outside influence.

Where the West search for the truth in the very existence of man, Japanese search for the truth and goal through emptiness and absolute mind enlightenment. The existence of the Ise Grand Shrine is a symbol of the whole Japanese society, based on the idea of vulnerability and ephemerality. The same way as the blossoms of Sakuras, the shrine comes alive again in its regular cycles. What a dramatic twist from the view point of the Western civilization which strives to preserve, maintain, and conserve the heritage of ancestors. The Japanese purposely choose presence as the way to eternity. The absence of the past refers them to the presence. Also the architecture of the cities changes much quicker than the one in the Western world. It gives impression of higher plasticity, more courage in its lines and form, it is designed for the present generation and lifestyle, so that it may vanish soon and be replaced by something new, more contemporary.

Cherry Trees

Why do we look with admiration on the Japanese after each earthquake as they tirelessly restore their homes without hysteria and strong emotions, in the same normal way as they go shopping or watching sunrise? Japanese thinking is based on positive “emptiness”, which in their view is not “nothing” but something from which actually everything stems. Positive emptiness or nothing is the centre of their cities, basis of their philosophy, centre of their thinking, spirituality, and the whole existence.

For the Japanese, every new visit of the Ise Grand Shrine is accompanied by the same desire to see the never seen treasure guarded by Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun. It is one of the three attributes of emperor´s power, mythical mirror closed in a circle case kept in the shrine behind the high barrier of the wooden palisade. This mirror is a metaphor of the Japanese society. It reflects something that does not exist, it is the substance of absence of everything and existence of nothing.

Existence of the Japanese is based on the permanent knowledge of the world´s ephemerality within a never changing cycle. That´s why their approach towards catastrophes and death is not as fatal as the Western one either. Acclimatization to natural catastrophes is their attitude towards the uncertain world. Their common perception of the world is based on instability and uncertainty. Japanese syncretism exchanged suffering of life for valorisation of the presence. It is not by accident that blossoms of Sakuras became a national symbol of the Japanese. Sakuras bloom just about ten days in a year and carry marvellous and fragile blossoms. This moment, which spontaneously repeats every year, is so important that it became a national holiday, celebrating the ephemeral beauty of these fragile blossoms.

The Ise Grand Shrine entered the UNESCO World Heritage Sites list as an “intangible cultural heritage”, happening in the space and time. It is an intangible symbol referring to the presence and the more monumental the more simple it basically is. Japanese knowledge altered Buddhist concept of existence which was accepted as a chorus of the succeeding reincarnations once ending in nirvana.

It is March now; Sakuras are blooming but soon they will start falling just to unfold their blooming beauty again next year.

Author: Iva Drebitko

Photo: Author´s archive