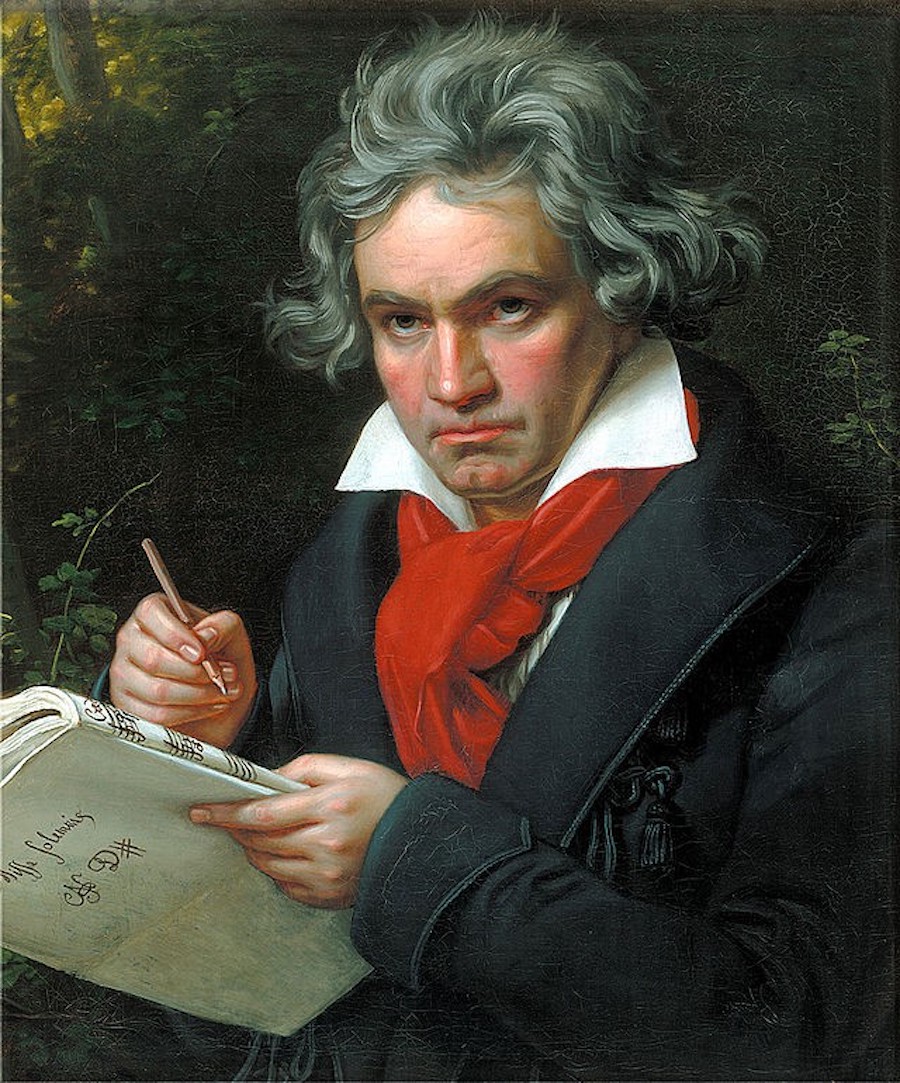

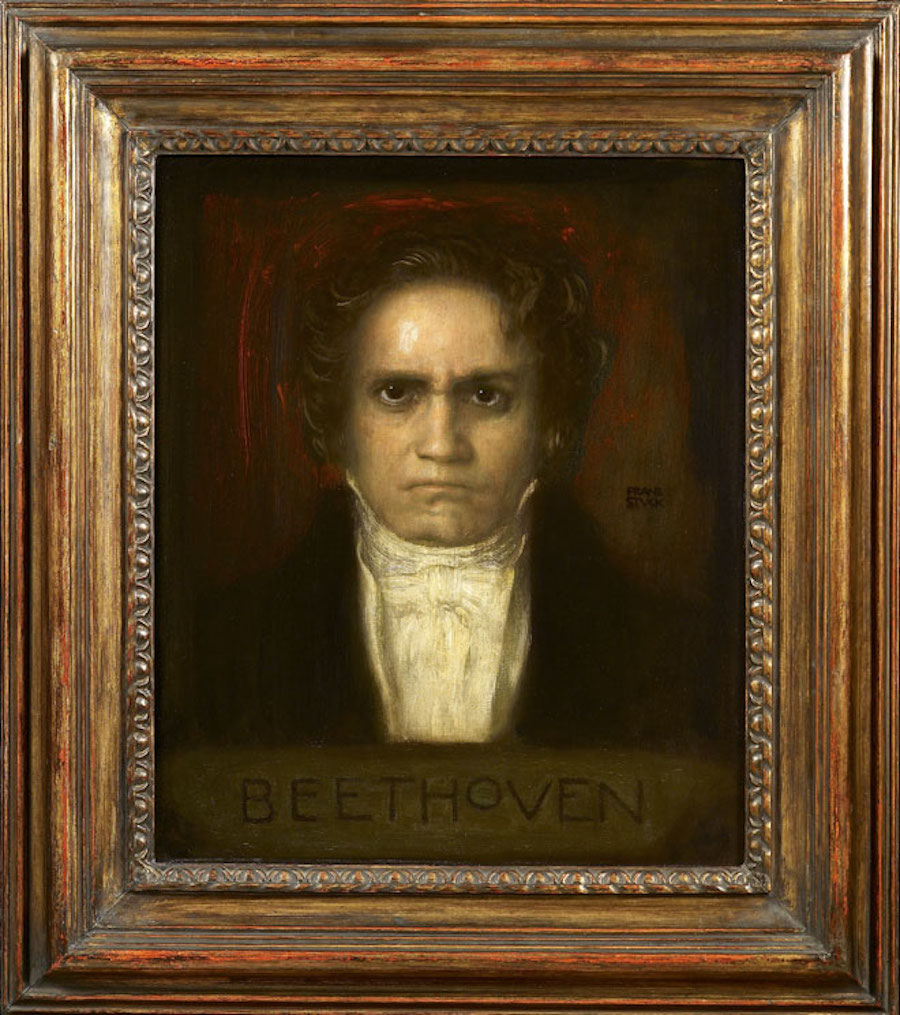

Ludwig van Beethoven was a complex being, gifted with unusual genius. What makes him even more extraordinary is the fact that although he was deaf he was driven by an insatiable need to create music. He left behind works which transcend their era and keep on enchanting, amazing and moving us all at the same time.

Beethoven was born in Bonn, Germany, on 16 or 17 December 1770. He had a wretched childhood. His parents had seven children, only three of whom survived into adulthood. Ludwig adored his mother Maria, but was terribly afraid of his father Johann, who was uncompromising, frequently drunk and, despite not being greatly talented at music, gave music lessons to children from aristocratic families. As a young child, Ludwig was endlessly amused by turning the iron handles of window blinds, listening with fascination to the scraping sound produced. His father soon discovered the young boy’s musical talent and began to cultivate it, likely also in the hope it could make him some money.

In 1787 at the age of seventeen, Beethoven made his first trip to Vienna, which soon became his adopted city. He was immediately captivated by the artistic life of what was then the capital of European culture, and after playing the piano in front of Mozart, Mozart told him: The world will one day remember you.

Beethoven’s stay in Vienna was unfortunately shortened by family drama. First he had to return to Bonn to be by the bedside of his dying mother, then shortly afterwards his youngest sister died. When his father lost his job, Beethoven was left to support his family. Following his father’s death in 1792, Beethoven returned to Vienna, this time to settle.

At just 28 years of age, when Beethoven was beginning to write his first symphony, the first symptoms of deafness began to appear. He tried all the procedures available at the time to treat it, with no results. From a hard-working and sensible young man, he became a crude and often violent man who could nevertheless express love and generosity. He helped, for example, in the acquisition of funds for the last living son of Johann Sebastian Bach, who was living in poverty. On another occasion, he gifted his new compositions to a charity concert for the Ursulines. Initially he was still able to hear a little, but in the final ten years of his life, he was completely deaf. He nevertheless continued to conduct rehearsals and play the piano until 1814. It is said that Beethoven could “hear” music through feeling its vibrations. Despite his dark nature, Beethoven found it easy to make friends. He studied piano playing with the composer Franz Joseph Haydn and, although their teacher- student relationship broke down, the men remained good friends. The young Beethoven also had the opportunity to meet Mozart’s “rival” Antonio Salieri – who legends say poisoned Mozart – in Vienna. Salieri welcomed Beethoven with great honour, and in return Beethoven dedicated three of his violin sonatas to him.

Over the years, Beethoven increasingly immersed himself in his music. He began to neglect his personal hygiene, being satisfied with merely pouring a bucket of water over his head rather than bothering with washing and bathing. During one of his favourite solitary walks in the countryside, he was even arrested by a policeman who thought he was a tramp. Piled up in his apartment were stacks of documents, which nobody was allowed to touch. He had four pianos, all without legs so he could feel their vibrations better. He often worked only in his underwear, sometimes even naked, and he could become so preoccupied with composing that he would not even notice when one of his friends came to visit him.

The anecdotes about his moodswings are legendary: throwing overly-hot food at a waiter, or sweeping a candle that someone had placed on the piano onto the ground in the middle of a concert. It is said that his frenzied behaviour was a response to the fear that he might lose the ability to perceive sound and music at any moment. He was therefore devoured by a desire to always create more, afraid he might not manage to inscribe everything that came to his mind in time. Despite his crude manner, he was generally respected and admired for the music he produced, and it was no surprise that his compositions often moved people to tears. His temperament and unrivalled talent were naturally appealing to women. Although he never married, he dedicated some amazing pieces to the women in his life, such as the Moonlight Sonata and Für Elise.

Beethoven lived during a period of turbulence. Europe was plunged into a crisis in which all aspects of human life would undergo massive change. It was an era of upheaval, not just in the way of thinking, but also in art, science and the social structures. Artists throughout history have utilised their talents to promote positions on various social issues. Beethoven, who lived during the period of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, at a time of deep social transformation and political upheaval, expressed his stances through music. In 1804 he wrote his Third Symphony, known as the Heroic Symphony. He initially dedicated it to First Consul of France, Napoleon Bonaparte, in whom he saw everything that was noble and glorious – a young, courageous man who could reach the very pinnacle of his bravery, talent and ingenuity and free Europe from tyranny, rising up against the oppressors, a personification of the motto of the French Revolution: “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity!” But when Beethoven found out that Napoleon had declared himself Emperor in May 1804, he tore out the title page in a rage and declared: “So he is no more than a common mortal! Now he too will tread under foot all the rights of man in order to indulge only his ambition.” When he had calmed down, Beethoven gave his work a new name, and thus the symphony is no longer dedicated to a “great man” but rather to the “memory” of a great hero. The original manuscript is today the property of the House of Lobkowicz, having been re-dedicated to Prince Joseph Franz Maximilian, a generous patron to Beethoven, and it is kept in the collection at the castle in Nelahovezes, Czech Republic. Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, was also based on living history. The story takes place in Spain, where a nobleman is unjustly imprisoned for threatening to reveal the crimes of a corrupt politician.

Beethoven’s violin concerto, the only one he wrote for the instrument, is longer and more complex than any that had been composed before it. In terms of its symphonic expression, it surpasses all of its predecessors. The piece is still considered today to be the most remarkable concerto in terms of all instruments together. As was common at the time, Beethoven composed it for a person, specifically the virtuoso Franz Clement. The lyrical wealth of the piece reflects all the subtelty of Clement’s playing. The third movement is a frantic rondo, into which the main theme is interspersed, interrupted by new elements. And the main theme declares a celebration of joy which Beethoven’s next work would return to.

During this era of great musicians, the aristocracy gradually came to appreciate music, and even to play some instruments. However, they considered composers and musicians to be their servants, and treated them as such. Beethoven was very progressive and independent, and rebelled against the status quo. “It is good to meet aristocrats, but only if they respect you.” When the nobility were having fun at a Beethoven concert, he would stop and call out, “I refuse to play for ignoramuses!”

Following a stay with his brother, Beethoven returned to Vienna in November 1826 in an open sleigh. He got pneumonia on the way and never fully recovered. In the late afternoon of 26 March 1827, the sky darkened, and a flash of lightning lit up his room followed by a massive thunder peal. Beethoven opened his eyes, rose up and shook his fist at the heavens. He then fell down dead. He was 57 years old.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s funeral was the last manifestation of the high esteem in which he was held by his contemporaries. More than twenty thousand people attented his funeral on 29 March, forming a huge honorary cortege which the soldiers present were unable to direct. Nine priests blessed the mortal remains of the great composer. He is buried in a grave whose location is marked with the symbol of a simple truncated pyramid, on which just one name is engraved: Beethoven. His remains lie next to the grave of Austrian composer Franz Schubert at the Vienna Central Cemetery.

Beethoven’s final words were: “I shall hear in heaven.”

Ing. arch. Iva Drebitko