Piazza Navona, Church of Borromini and the fountain of Bernini

One of the things Rome is known for is its magnificent architecture. On every corner, wherever you look, you’re greeted with an incredible fountain, statue, building or church. Yet few today realise that the greatest examples of Baroque art in Rome in fact came about through the passion, jealousy, hatred and petty ego displayed between two Italian architects, Bernini and Borromini.

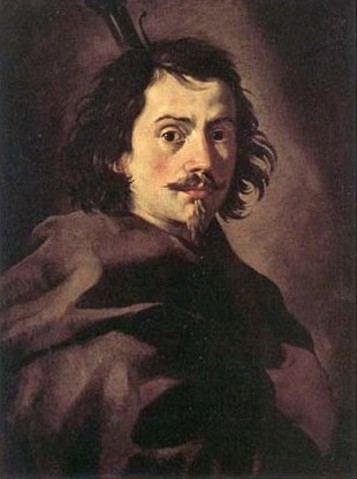

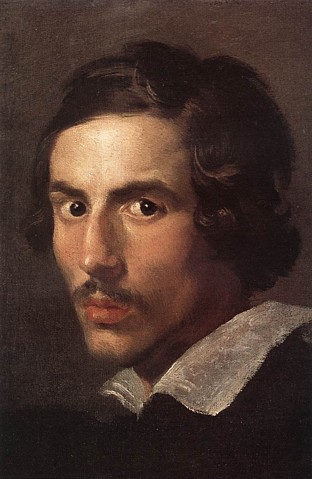

The two were as different as they come. Bernini was charming, well-spoken, well-mannered, from a wealthy family and always impressed by witty banter, even in the presence of the social elite. In contrast, Borromini possessed absolutely none of Bernini’s charm. Borromini was brash, had a lack of self-control, angered easily and showed his emotions. Yet he was an incredibly talented architect who suffered from what we today call depression. Bernini and Borromini clashed professionally for many years. They reluctantly worked together on Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, where Borromini began to feel overshadowed by Bernini. It wasn’t so much the difference in their personalities which gave rise to the creative feud over Piazza Navona, but rather something less comprehendible. “I don’t mind that I don’t have the money,” said Borromini, “but I do mind that he does not honour my work.”

Detail of a statue with a raised hand by Bernini in front of the church by Borromini

Their dispute was taken to an entirely new level in 1644 when Cardinal Giovanni Battista Pamphili was elected Pope Innocent X. Innocent decided to transform a lacklustre space in the centre of Rome into a grand plaza worthy of him and his prestigious family. When his vision for the Piazza Navona came to fruition, Innocent decided it needed a focal point: a central fountain incorporating a large Egyptian obelisk. Innocent was a great fan of Borromini’s inno- vative work, so he was quick to choose him as the architect to extend the Acqua Vergine aqueduct for his fountain. Borromini also suggested that the fountain should have four specific sides, representing the world’s four great rivers: the Nile, the Danube, the Ganges and the Plata. Satisfied with this proposal, Innocent asked Borromini and a handful of other architects to submit their designs for his new fountain.

In the end, and to the surprise of all of Rome, however, Innocent chose Bernini to design his fountain, and Borromini to design the Church of Sant’Agnese in Agone, which was to stand right opposite the fountain. Borromini was outraged that his ideas had been given to his rival, so he allegedly decided to make subtle changes to the church in order to get revenge for Bernini’s fountain. It is said that Bernini designed the figure Rio de la Plata with one raised hand to protect himself from the forthcoming fall of the church built by Borromini. There is another myth that the Nile statue is hiding under a veil not because the river’s source was not yet known, but rather because he didn’t want to gaze upon the bizarre design of Borromini’s church. Borromini is said to have claimed that in the feud with his rival, he added a small statue of Saint Agnes to the base of the church’s bell tower. This statue stands with her hand over her heart, allegedly worried that Bernini’s fountain will soon collapse because it was built without soul and cannot hold the weight of the great obelisk.

San Carlo alle quattro fontane

No proof has ever been found that these two architects did in fact make these subtle design changes to spite each other. But one thing that is very clear is that this life-long feud gave Bernini and Borromini the fire they needed to complete most of their absolutely best work. The crowning glory of Borromini’s architectural skill was his final building, the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1638 – 1667).

Borromini

This work aroused unusual enthusiasm and admiration from experts and the lay public alike, and its renown spread well beyond Italy’s borders, likely influencing Europe’s Baroque architecture at that time. Borromini impressed all the builders there with his revolutionary solutions to problems. He had to be constantly present to guide their hands so they could grasp his plan. It was far removed from the proven rules of construction in that he created shapes which appeared to disobey the rules of gravitation, purely through his absolute mastery of construction techniques. He worked in close accordance to geometric patterns. The church’s design was highly intricate and based on two triangles positioned together. Two circles are drawn within, together creating a perfect oval. Its façade, completed after Borromini’s death, corresponds precisely to the wave of movement generated by the spatially complex interior. Bernini himself said he had never seen anything so incredible before. The church interior is plain and entirely white, without the richly gilded ornamentation commonly used in Baroque sacral architecture at the time.

Bernini

Bernini’s Sant’Andrea al Quirinale church was his response to Borromini’s great work. This church is also relatively small. Its construction took 12 years (1658-70) and it was also built late in his career. This oval building with chapels set into the external walls relies on the precise design rules created by Michelangelo. Bernini’s mastery is in his use of optical effect, with dark marble illuminated using cleverly designed side roof ports, lending an additional dimension to this small construction. In 1660, Borromini began to lose spirit. The fame and success of his rival Bernini was getting to him more and more. Work on his next project, Sant’Andrea delle Fratte, had come to a halt and his façade of St Philip Neri had been disfigured by lateral extensions. He travelled to Lombardy, but he began to suffer from melancholy upon returning to Rome, not leaving his home for whole weeks at a time. As his condition deteriorated, he burnt all his drawings, became sick and began suffering from hypochondriacal hallucinations. The decision was then made to force him to abstain from all activity so he could sleep. During one hot summer night, unable to work or relax, he got up and caused severe injury to himself with a sword. After inflicting this lethal injury, he repented, received the last rites and wrote his will. On his request, he was buried anonymously in the tomb of his teacher and friend, Maderno. Borromini’s architecture, almost forgotten during the course of the 19th century, was recognised as a work of genius in the 20th century, and both architects are today considered the absolute masters of High Baroque.

Author: Ing. Arch. Iva Drebitko

[…] Feud of the Fountain of Four Rivers: https://www.czechleaders.com/iva-joseph-drebitko/an-architectural-feud-that-inspired-the-creation-of… […]