“You really have to have a passion for what you do.”

Dr. Jack Wilson, entrepreneur, innovator, scientist, educator and philanthropist.

Kind words from Mr. Wilson to Czech and Slovak Leaders Magazine:

I want to thank you and compliment you on the superbly professional job that you and Miriam Margala have done with the interview. I have done many interviews in my career, but this was certainly one of the most professionally done. The editing was excellent and the production values of the magazine are exceptional. I have gone on to the Website to read some of the other interviews -which are equally well done. You have created a fine resource for the region. Miriam Margala managed to capture the messages that have inspired me over the years. It was a terrific job.

It is not easy to try to make justice describing somebody as accomplished as Dr. Wilson – a former university president who worked and interacted with congressmen, senators, governors, four US Presidents; an innovator in all his endeavors: the founder and CEO of what became a $500 million IT company, the founder of a successful online university school; a fundraiser (during his presidency, the funds raised more than doubled); an educator, mentor and philanthropist and so much more. I therefore asked for comments from some of Dr. Wilson’s closest colleagues, themselves nationally and internationally recognized educators, administrators and politicians, as the most fitting way to introduce him to our readers.

Current University of Massachusetts President and former long serving US Congressman Marty Meehan puts it very aptly when he says that “Jack is a pioneer in cultivating and catalyzing innovation and entrepreneurship. His success as an academic, researcher and entrepreneur allows him to bring unique perspectives to the larger conversations around entrepreneurship.” Dr. Jacqueline Moloney, current University of Massachusetts (UMass) Lowell Chancellor, the first woman ever in that role, further emphasizes Dr. Wilson’s expertise and influence when she explains that a strong “commitment to entrepreneurial thinking drives Jack Wilson. His expertise is a tremendous asset to our students, to his colleagues, to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and to the Nation.” Dr. Wilson’s vision of economic prosperity and its connection to university research is eloquently described by Associate Vice-Chancellor for Entrepreneurship and Economic Development at UMass Lowell, Steve Tello, who notes that “as past Chair of the National Council for Innovation, Competitiveness and Economic Prosperity of the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, Jack championed the need for higher education, industry and government to work together. He understands the important role universities play in promoting innovation and economic development, and as President Emeritus of UMass, he continues to support these efforts as a teacher, researcher and entrepreneur”.

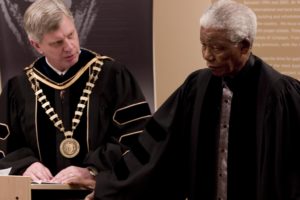

I am quite sure that Dr. Wilson’s life long curiosity and interest in anything that can possibly make a difference immediately or in the long run and his ability to get people to work with him is due to his personal charisma, enthusiasm and willingness to always listen to other people’s opinions. He feels just as comfortable talking to his undergraduate students as to influential CEOs, politicians or such luminaries as Nelson Mandela, upon whom Dr. Wilson bestowed an honorary degree (pictured).

Dr. Jack Wilson with Nelson Mandela

Anything Dr. Wilson discusses is inherently infused with the underlying notion of doing good. To use the words of the former highly liked and respected UMass Lowell Provost, Dr. Don Pierson: “Jack Wilson is a tremendous asset to the expansive community he influences. He is a charismatic leader, a wise mentor, a trusted colleague, an inspiring teacher, and a generous benefactor.”

Dr. Wilson, thank you very much for this opportunity to talk to you. I will open our conversation with a task for you – how would you describe yourself in a few words?

I have a phrase that I always laugh about that appears at the end of every job description: “and other duties as assigned”. Pretty much every job I’ve ever had and the way I’ve lived my life was – other duties as assigned. I like to look around for things that I believe should be done and then try to figure out how to get them done. I particularly enjoy it when I’m told that many tried and failed. That’s like waving a red cape in front of a bull – I am ready to charge. That’s how I became a scientist or an entrepreneur – scientists do not want to research something everybody understands, they will go and research something nobody understands. Entrepreneurs do the same – look around for things that should be done, could be done and haven’t been done. For example, when I did research in liquid crystals back in the 1970s, nobody thought it was terribly interesting or useful. But I thought it was – and my group (one of only a few) quickly discovered we could make display devices using liquid crystals. I built some of the first liquid crystals displays ever. Even though many large American companies became excited about liquid crystals, at the end, they did not have the foresight to see how this was going to change the world. However, there were plenty of people from Japan visiting my laboratory interested in liquid crystals. And today, as we all know, we buy all the liquid crystal display devices from Japanese and Korean companies that exploited that technology. I will admit that looking for things that haven’t been done but could and should be done may lead to a somewhat eclectic life.

Why do you say ‘admit’? Isn’t it good to have an eclectic life?

Oh I believe it is good to have an eclectic life but many of my colleagues would disagree. They prefer to focus on one thing only. Instead, I looked around for problems I could solve to make a difference.

This leads to an interesting question – the idea of a career as climbing the typical ‘career ladder’ is becoming obsolete. Instead, one should look for opportunities. You are an interesting amalgam of both. Your academic career seems to have been the typical university ladder path (professor, chair, dean, provost, president), but you have also been incredibly entrepreneurial, turning your research into a business; you ventured outside academia to take on jobs that indeed were all about solving problems as they came.

I did both, that’s true – but I was also quite lucky. I did climb the ladder, but only because it presented interesting problems to be solved. I followed things I was curious about – and was often

criticized for it. When I moved away from the hardcore physics into computational physics, people said that I was abandoning my field to play with these toys called computers. But I quickly became a leading person in developing computers for complex problem solving. Eventually, I got hired as a consultant by AT&T, IBM and others. But I did not become interested in this area because I would be hired by them; I went into the field because I found it interesting. When I was still far too young, I was asked to become a department chair. I said yes because I saw it as an interesting thing. Pretty much, as I kept looking for interesting problems to be solved, every job thereafter was something that came to me through serendipity – even becoming the President of the University of Massachusetts.

Curiosity is certainly something strongly associated with you. When people are curious enough they put themselves out there and become noticed – and then things happen…

I think that’s true and I’ve tried to teach my students the same thing. Instead of planning your future in a systematic fashion, you should learn as much as you can about as many things as you can and do interesting things that make a difference. Don’t take on problems that are easy to solve; take on hard problems, di cult to solve. Besides, it’s fun taking on harder problems and a huge joy to win on them. You don’t always win but you do get noticed. That’s how the University of Massachusetts asked me whether I’d be interested in starting their online school. I said yes. I’d realized early on, before UMass asked me, that having only the in-class model of learning meant locking the people who could not come to classes because of their jobs or families out of education. I thought – we could use technology to provide education for them. I started developing this technology and eventually, built a successful company offering online education. So when the University of Massachusetts asked me whether I would build an online school for them, I said – when can I start? Today, UMass online enrollments reached 75,565 students. In terms of the revenue, we surpassed $100 million. It was definitely worth it, to go and give it a try, to solve a difficult problem and make a difference.

Your eclectic career spans almost 50 years. What drives you? What inspires you?

Seems like a long time, but I keep changing what I’m doing every few years. I still find new interesting things to do and am still able to make a difference. I am opportunistic in a sense that I don’t systematically plan ahead. When I become aware of a thing that needs to be done, should have been done a long time ago but wasn’t, people tried and failed – then that’s an opportunity for me to give it a try. A good example would be our UMass Law School. There was no law school when I became President and founding a public law school was not on the list of my priorities at all. If it hadn’t been for a young woman who recognized and approached me in a restaurant one night, asking me upfront why UMass didn’t have a public law school, I may have not paid attention to it. There are many private, expensive law schools – which is where she got her degree and ended up with a huge debt to pay off. She wanted to make a difference and do public interest law but couldn’t because of her debt. I realized she was right. For 150 years, Massachusetts had been failing its citizens because it was not providing them this opportunity to study law at a state law school. I recognized that founding a public law school should be done. There was a lot of negative publicity, especially from all the established private law schools. But I persevered and today, the University of Massachusetts has a public law school, fully accredited and fiscally healthy. It was a problem that was far away from how I started: a scientist, physicist, engineer, entrepreneur. But it was a problem that needed to be solved and an opportunity to make a huge difference – and that always drives and inspires me.

It seems that stepping out of your comfort zone is something you seek and enjoy; it seems to be your mode of operation.

(Laughing) Yes, that’s true. To be fair, I like to step out of my comfort zone if it allows me to do something that should be done – not just for the sake of it. But I have to admit I do enjoy stepping out of my comfort zone if it means making a difference.

I have known you professionally for a few years now and I think that “the sense of purpose” is not a cliché for you but has a strong moral and ethical value. Could you address this in more detail?

I agree with you. When you hear the phrase today, oftentimes it’s way too high minded. But there is a sense of purpose: I have certain skills and talents, one of which is a thick skin so I can endure things that other people perhaps could not. I certainly can take a punch. I do not like being hit of course, but I don’t mind it either if we’re getting done what needs to be done. To me, the sense of purpose means that we’re all stewards. Each of us is given about 80, 90 years and we’re going to have to use these years productively. It’s like a relay race – it’s a metaphor for life. Somebody picks up the baton and runs as fast as they can then hands it to the next person who runs as fast as they can …and so on and so forth. So in life, people hand you a baton – run! Do all that you can. Get it done! At the end, I want to be able to say – ok, I did my part. I made some mistakes, I didn’t get everything done, but the next runner may get it done…

And that takes me to the question of leadership. Again, in your case, it means something very concrete, tangible. When you became President of UMass, the first thing you did was to change the old, entrenched attitude of certain defeatism since the university is part of an educational landscape where there’s far too many elite private universities (Harvard, MIT, Boston University, etc.). You successfully and fast changed this into the sense of pride for all those who work and study at UMass. How did you get about 70,000 students and 17,000 staff to change their attitude?

Well, I don’t know how much credit I deserve, because that’s just the way I am. I don’t accept defeatism. I get most frustrated when I see uncommitted people. Frankly, it irritates me and that makes me very assertive and pushy. One of the statements I made when I felt irritated was: “the path to economic and social development in Massachusetts goes through UMass” (now an iconic and still applicable statement, MM’s note). Of course I knew it was going to be controversial. The truth is even my friends, Harvard, MIT and BU presidents themselves told me I was right! Naturally, the press criticized me. But I had statistics – 80% of all our workforce come from UMass! One of our medical school professors is a Nobel prize laureate. We have hundreds of millions of dollars in research grants. Our alumni work as CEOs and other high ranking officials in the biggest companies here in Massachusetts and elsewhere. We should be all excited about that! The University of Massachusetts now leads as an institution in many measured aspects of higher education.

Dr. Jack Wilson with Barack Obama

What are the most fundamental characteristics of a successful leader?

That’s a tough question – it’s a multidimensional issue. To put it simply, you have to care and be passionate about things that are important, not yourself. True, most leaders have a strong ego; they must believe that things can get done. But you really have to have a passion for what you do. In my case, I was very eclectic about the things I cared about. It could be physics, engineering, education or entrepreneurship, which I am a great believer in. Entrepreneurship has created great futures in many places. If you look at places that are not entrepreneurial, it’s been very tough for them. But if you encourage entrepreneurship, you see great things happen because it fosters innovative and engaged individuals for whom problems are opportunities to come up with innovative solutions. Even if they fail at the beginning, entrepreneurs do not complain but ask – why? What do we have to do differently to succeed? What did we learn from the failure? I think a great leader also has to think this way.

Looking at your philantrophic works, you seem to get a lot of satisfaction from becoming involved in making education available to as many people as possible. You have established a scholarship fund, an entrepreneurship center at UMass Lowell; you give freely your time to educational projects. Why is philanthropy important to you?

Philanthropy is important to me because I recognize that I have been an incredibly lucky person and have benefited from help that makes me want to give that same, or better, opportunity to others. I think that most people find that when they are able to help someone else, that it provided a very strong feeling of satisfaction and involvement. I am lucky to have lived long enough to see students that I have taught, or people that I have helped, who have gone on to make tremendous contributions to the world. I hope that they can find the same satisfaction in their lives that I found in mine. This means that satisfaction can be passed from generation to generation. Living in this way makes for a joyous life.

Let’s talk about your company and IT entrepreneurship. You’re the founder of an IT company, the LearnLinc Corporation – which was eventually worth $500 million.

Correct, it could be easily characterized as IT entrepreneurship because we had to solve various information technology problems, networking, communication, computing, etc. However, our number one priority was always trying to connect communities of people who wanted to learn together, better and faster. We had to solve many technological problems but that’s not why we founded the company. It eventually became very successful and later underwent various mergers – in early 2001, the company’s market value on NASDAQ was $500,000,000 dollars. Again, our goal was not to build a company and then to sell it for a lot of money. It was creating learning communities and helping them interact online. I saw that as something not only interesting but also something that, even back then, I believed would later become an important way of learning.

Eventually, you sold your company. You were its founder, CEO and chairman. Was it difficult to move on – more generally, how do you know when to let go and stop?

Knowing when to stop is one of the most important and difficult tasks in anyone’s life. I have seen too many people who have hung on to a role far longer than they should have. That hurts themselves as well as others. It is important to refresh oneself regularly and for those around you to experience fresh leadership. I decided that I would try to make a major change in my work every 7 to 10 years. I have held to that principle for my entire career. You need to make a reasonable commitment to anything that you start, but after 7-10 years, you should have accomplished your goals -or you probably never will. In either case, it is important to let new leadership take the organization in new directions. Now that I have done this six times in my career, I will say that sometimes it is hard to let go, but I have never regretted doing so. I have always found new and meaningful projects to work on next.

As a business professor and a successful entrepreneur, how do you prepare your students for mistakes or failures? The truth is simple – you cannot become an entrepreneur if you cannot bear the pain of mistakes – can it be taught?

We do try to teach students about failure and how to overcome it. We try to teach them that every mistake and failure, however painful, is an opportunity to learn and become better. But you’re quite right to say that it’s ‘easy’ to lecture about it. The best way to learn is of course to actually go out and go through that failure and have a mentor that helps you face the challenge. I have tried to mentor people through failures and help them understand that when they’re in the depth of pain of getting punched hard that it is just another learning experience. Mentoring is an important part of entrepreneurship. We have a couple of ways in which we offer it to our students. First, we bring in successful entrepreneurs who have gone through failure often more than once. Second, we try to see if we can find in the student’s own background some experience of failure and use it constructively so they themselves can see what they learned from it. But I think in the end, to have a mentor to help through experiencing hard challenges is absolutely the key.

Clearly, it is also about persistence as an overall attitude.

To be an entrepreneur you certainly have to be persistent. You try to solve a problem, you get beaten down, then you come back, you try again, differently. And if it still doesn’t work, you repeat the process. I call it “the Ps”, passion and persistence, trying again and again. Oftentimes, entrepreneurs are seen as impatient. In fact, many entrepreneurs had had a career in a larger company where they became a squeaky wheel, even annoying. They didn’t like the way things were done and they saw there was a better way. They wanted to implement their ideas, but to bring about change can be incredibly difficult in a large, traditional company. So many of them become entrepreneurs. If they cannot implement their ideas within the company, then they leave and start their own company.

In your career, you have had to deal with all sorts of people. At one point, you had to work with both Ted Kennedy, an iconic democrat, and Mitt Romney, who was a Republican governor. What does it take to be an effective communicator?

There are different approaches to communication. There’s the manipulative approach where somebody tries to talk to people and say what they want to hear. Then there’s the communicative goal where you listen and try to understand the other. You don’t have to agree with a lot when you listen to them. Indeed, I have had the great opportunity to visit and talk to quite a few American presidents. I even met our latest president (Donald Trump) who I will say is very interesting to speak to. I’ve never had a problem communicating with other people, whatever their beliefs are, because when I meet them I want to learn about them. I want to see what makes them tick, what they’re interested in and I don’t have to feel I am advancing my point of view. I might, depending on what we’re talking about, but that’s not the goal of communication. Learning is the point of communication for me.

You have traveled extensively; you are enthusiastic about globalization – can you discuss its importance and impact?

I traveled in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union before the Iron Curtain came down. I watched these countries cope with a very different economic system; I watched Russia go through many changes. I watched communist Europe become free. I also spent a lot of time in China where they’ve undertaken a very different path. You learn a lot through traveling and actively engaging in international projects and I encourage my students to get international experiences, to immerse in different cultures but at the same time I try to make sure that they have exposure to the culture here in the US. For those that can’t travel, I teach a global entrepreneurship course. I teach about the differences in the economic systems, entrepreneurship attitudes and free trade. Obviously, I am a huge fan of globalization, of free movement of ideas, of entrepreneurship across borders, of free trade. I recognize that trade hasn’t always been as free or smooth as it should have been and that we always have to be looking at how to make sure that different countries benefit as much as they can from free trade. I believe there are no benefits to isolation. We can all learn from each other, we all bring good ideas we can share and work on developing them together.

How do you see Europe as an ‘international’ American?

First of all, my own heritage is European – Bavarian and Austrian. I grew up in Pennsylvania which was very much affected by European culture. Specifically, by people from Central Europe – Germans, Czechs, Slovaks, Polish. Later, I was able to visit these countries. I had applauded the rise of the more unified Europe; I admire the changes in Europe. I used to go through Check Point Charlie in Berlin during the old Iron Curtain times and that was no fun. Today of course, it is very different – much more free and it’s a much better world. I watched the excitement of all the communist countries after the Iron Curtain went down; I observed their aspirations and optimism. But also a degree of disappointment – they succeeded in building a pretty healthy economic system but it takes a lot of time for the economy to fully develop, to make sure everybody has a chance to participate in it. Some of that has been done very successfully and some still needs to be done. And that’s true also in the US and elsewhere. That’s another reason why globalization is so beneficial. We can all work on making sure that everybody has a chance to participate in a healthy economy.

What do you say to those who claim that globalization brings in a degree of homogenization which is counterproductive?

This criticism is a bit tricky to address because in fact globalization does mean that cultures are exposed to each other and adapt ideas from each other. How much of that is good and how much is bad? We certainly see countries that try to preserve their identity and almost regulate it. Does that work? If we consider history and go back to the trade between Europe and Asia during the Silk Road era, we realize how cultures have influenced each other for millennia. We think that spaghetti and meatballs are a typical Italian dish but it was brought in and adapted from China. Or consider Japan. Their entire written language was adapted from China. So is it a bad thing? A good thing? I think it’s neither – as long as it works for a particular culture.

I will also say that to a certain extent, the argument of trying to protect one’s culture is of course valid. I do like to see cultures and languages preserved but I don’t like to see taken this to a point where you try to refuse ideas from other cultures completely. The world has advanced by borrowing ideas from each other, taking and shaping them according to the needs of a particular culture. That’s how I see globalization – sharing, adapting and exchanging freely.

By Miriam Margala

Dr. Miriam Margala enjoys a rewarding and eclectic professional career. She is a university lecturer, teaching academic writing, communication and philosophy of language. She mentors other professional women through an organization based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Women Accelerators, where she is a member of the Board of Directors. She also translates literature, both poetry and prose, writes academic articles, conducts interviews for various publications, presents at international conferences and is involved in international projects dealing with innovation in education and diversity in industry. She is also involved in art projects both in the United States and Europe.

Dr. Miriam Margala enjoys a rewarding and eclectic professional career. She is a university lecturer, teaching academic writing, communication and philosophy of language. She mentors other professional women through an organization based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Women Accelerators, where she is a member of the Board of Directors. She also translates literature, both poetry and prose, writes academic articles, conducts interviews for various publications, presents at international conferences and is involved in international projects dealing with innovation in education and diversity in industry. She is also involved in art projects both in the United States and Europe.